Dictators and criminals fear this USC instructor who’s making the case for an Oscar

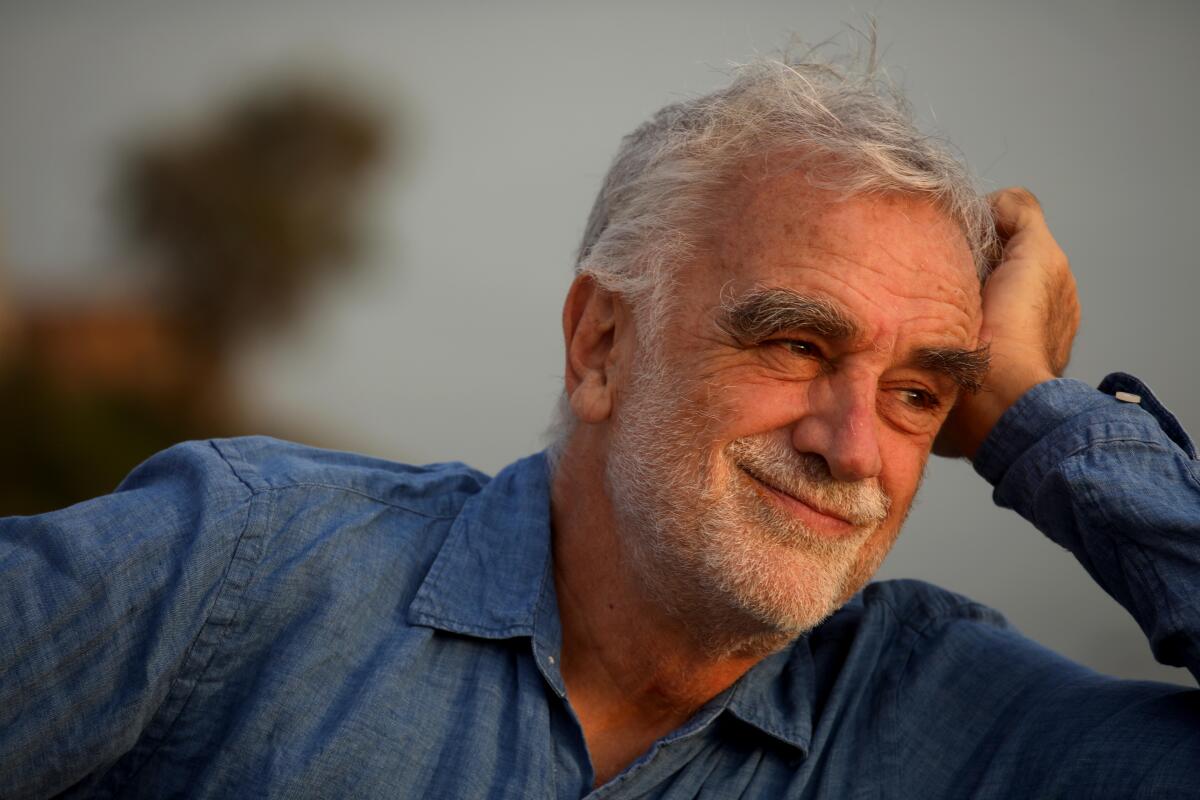

The Argentine lawyer Luis Moreno Ocampo, who has put the screws to genocidal strongmen and placed dictators behind bars, isn’t sure whether Donald Trump should be tried for the Jan. 6 riot.

He thinks no ruler is above the law, of course. And it’s clear from his remarks on the Oath Keepers and their ilk that he’s been watching the damning facts pile up against Trump.

But despite his penchant for passionate outbursts — “It’s crazy, it’s insane!” he’ll exclaim over some or other outrage or absurdity — Moreno Ocampo is known as a judicious and meticulous compiler of material facts. That’s one reason why he was chosen to help create the International Criminal Court at The Hague and spent nine years as its chief prosecutor, then went on to teach at Stanford, Harvard and for the past three years at at USC

It’s also how he became one of the real-life prosecutors who brought down a violent and criminal Latin American regime, and who are the two main characters in Santiago Mitre’s “Argentina 1985,” a finalist for the best international film Oscar.

So if he were Merrick Garland, would he make the 45th U.S. president take the stand?

“I would need to see the evidence, really,” says Moreno Ocampo, barefoot and tilting back in an Eames chair. “The issue is not about Trump. The issue is, who is today supporting a mob rebellion against the Congress?”

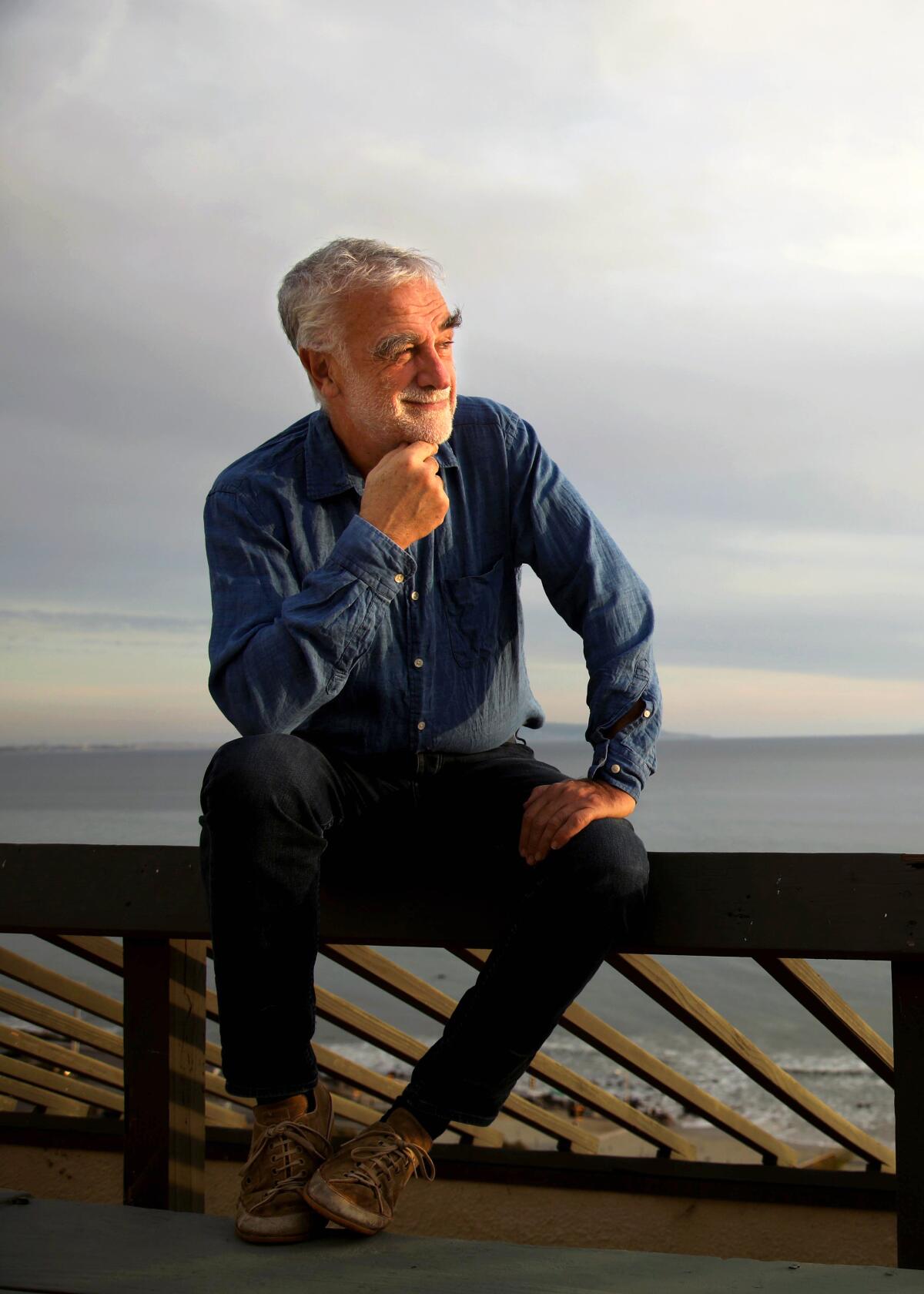

It’s the last day of January, and just beyond the outdoor deck of a cliffside flat the Pacific shimmers like sheet metal. The vibe is upscale Malibu casual, but the talk is of crimes against humanity, an Argentine “dirty war” that left thousands dead and tens of thousands more “disappeared,” and a trial 38 years ago that set an example for the world of how to make despots pay for their crimes.

Back in the early 1980s, Moreno Ocampo wasn’t an urbane 70-year-old man of the world, but a young, very green attorney who’d never prosecuted a single case.

He was an unlikely choice as co-counsel to Julio César Strassera, the esteemed veteran barrister who mustered the gruesome evidence against Lt. Gen. Jorge Rafael Videla, Adm. Emilio Eduardo Massera, Brig.-Gen. Orlando Ramón Agosti and other henchmen of the Argentine military junta that overthrew President Isabel Perón in a 1976 coup then imposed a seven-year reign of terror on their nation.

As the movie dramatizes, Strassera (played by Ricardo Darín) thought the relative inexperience of Moreno Ocampo (Peter Lanzani) actually was a plus. There was no precedent for such a dangerous and consequential legal undertaking, so it would require a daring, creative approach to assemble the case — a flair for innovation and improvisation that Strassera glimpsed in his young associate.

Moreno Ocampo recalls, “Julio said, ‘We have the flexibility to invent something here, because the police cannot investigate this crime — they were involved in the crimes. And the system is so slow, and I only have four months. So you conduct the investigation. Invent something!’’’

Not for the first time, Moreno Ocampo lets out a laugh that lands somewhere between a cackle and a guffaw — a gackle — which may seem surprising from a guy who’s stared so long and hard into the abyss: digging into the genocide in Darfur; investigating Libyan dictator Moammar Kadafi for crimes against humanity; prying open the brutality of Joseph Kony and the Lord’s Resistance Army, whose tactics while rampaging across four African countries included mutilation and child-sex slavery. He sets down an insider’s view of his experiences in his book “War and Justice in the 21st Century: A Case Study on the International Criminal Court and its Interaction With the War on Terror,” published last November.

UCLA Law School professor Kal Raustiala, who has known Moreno Ocampo since they both taught at Harvard Law School, says the qualities his friend displayed in devising the case against the Argentine junta served him well while helping set up the prosecutor’s office of the International Criminal Court (ICC) in the Netherlands when it was established in the late 1990s and early 2000s. It remains the first and only permanent international body granted jurisdiction to prosecute individuals for genocide, war crimes, crimes of aggression and crimes against humanity.

“No one knew what this tribune would end up being like, whether it would be a total failure or a roaring success,” says Raustiala. “His boldness and his willingness to take those kind of chances is probably the most striking thing about him.”

These days Moreno Ocampo is exploring international justice not in the courtroom but in the USC classroom, where he often collaborates with colleague Ted Braun, a filmmaker whose “Darfur Now” prominently features Moreno Ocampo in his ICC role. They tag-teamed a class on “War, Justice and Global Narratives in the 21st Century,” deploying celluloid texts like “The Battle of Algiers,” “Judgment at Nuremberg,” “The Act of Killing” and “Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith” to analyze the morality of state-sanctioned violence and the rhetorical ambiguities of revolutionary “terrorism,” among other themes.

In one class, Braun and Moreno Ocampo led their students in deconstructing the legal distinction between “enemy” and “criminal” combatants as it applies to Mace Windu, Anakin Skywalker and crew.

“We engaged the students in a very heated discussion about the judicial status of the Jedi,” says Braun, who encouraged his friend to make the jump from Harvard to Southern California. Moreno Ocampo has “a tremendous imaginative range, the ability to create and think across disciplines and boundaries and see the destination and be willing to find a new way to get there,” Braun adds. “It’s like playing soccer with Messi.”

Moreno Ocampo believes that film and other mass media are indispensable tools in shaping and interpreting history. His reverence for Steven Spielberg movies like “Saving Private Ryan,” “Lincoln” and “Munich” borders on the religious.

“Spielberg is Shakespeare for me,” he says. “Spielberg is an actor in U.S. life because he defines narratives. The most important American weapon is not the Pentagon. It’s Hollywood.”

Another USC colleague, Viet Thanh Nguyen, who fled Vietnam with his family, has written, “You fight your wars twice: first in the battlefield, then in the memory.” Moreno Ocampo agrees, pointing out that his own book about the Argentina trial sold around 10,000 copies, whereas the Amazon-distributed “Argentina 1985” will be seen by millions.

“The movie crosses 40 years and reaches with the same message to a new generation,” he says. “My youngest kid is 23, he had no idea what happened. Now he’s learning with the movie.

Mitre, the director of “Argentina 1985,” who was 4 years old when the real trial took place, credits Moreno Ocampo’s insights with enhancing the film’s authenticity and accuracy.

“I was afraid of Luis at the beginning,” Mitre says, laughing. “He’s an icon. And Luis has very strong opinions [about] where he thought I should go. So it was a lot of fun, our first meeting, because I was wanting to ask him questions about the trial and he was the one who was interrogating me.”

For his part, Moreno Ocampo credits the film’s courtroom verisimilitude to Mitre and Argentine producer Victoria Alonso, who “understand very well these John Ford movies on justice.”

“All the scenes in the court are absolutely verbatim,” Moreno Ocampo says. “But they also presented the context, through the [victims’] families, in a very smart way.”

A true porteño (port-city person), the nickname given to Buenos Aires denizens, Moreno Ocampo is zealous about soccer and literature. He flew back to the capital in December to watch Argentina win the World Cup final with his kids. A poster of “Argentina 1985” leans against his stylish bachelor pad’s white walls. A volume of Borges rests on the coffee table.

“Borges is a genius,” says Moreno Ocampo, adding an expletive, who served as legal counselor to another Argentine [expletive] genius, Diego Maradona, the football superestrella.

“I knew Maradona very well. He was an artist. He was so poor. And then he became the most famous person in the world — from a person full of limits, to no limits. So he became crazy. But when I met him he was a lovely, lovely young boy.”

To outsiders, Argentina may seem like a Borgesian funhouse of mazes and mirrors, ruled by Peronist populists and their glamorous spouses who get turned into Broadway musicals. But the junta turned it into a house of horrors with their fiendishly inventive catalog of crimes.

Children belonging to leftist parents were kidnapped and given away for adoption to supporters of the dictatorship. Citizens branded as subversives were stripped, drugged and tossed from airplanes into the Río de la Plata. “Argentina 1985” recounts the actual testimony of a terrified pregnant woman who spontaneously gave birth after being tossed in the back of a police car.

For Moreno Ocampo, the politics of the dirty war were personal and familial. His grandfather was a general and his mother’s two brothers were colonels, one of whom visited Gen. Videla in prison during the trial to apologize for his nephew’s behavior and promised that he would never speak with Moreno Ocampo again. He kept his word.

“I betrayed him, I betrayed the family, I betrayed the army!” says Moreno Ocampo, exulting in the anecdote. But in the end he also changed the mind of his mother, who like many conservative Argentines had applauded the junta for ostensibly bringing “order” to a chaotic country.

“It’s true what the movie shows, that my mother changed after she read about the witness who had the baby in the police car. She called me and she said, ‘I still love Gen. Videla, but you are right. He has to go to jail.’ And that for me was a huge thing.”

Argentina has won the international film Oscar twice before, for “The Official Story” (1985) and “The Secret in Their Eyes” (El secreto de sus ojos) (2009), which also starred Darín, making it the first South American country to win that award twice. Both those films also deal with the dirty war’s legacy. “The Official Story” is about a middle-class Buenos Aires couple who realize that their illegally adopted child may have been born to one of the desaparecidas.

Moreno Ocampo saw it while working on the trial depicted in “Argentina 1985.”

“I never cried when I was looking for the evidence. I saw awful things — I never cried. But I cried at the movie. Because without my professional protection, the movie invaded me.”

He’ll be at the Oscars ceremony on March 12. If Argentina wins for the third time, he says, it’ll be as good as Maradona or Messi scoring three goals in a game.

“A hat trick,” he says.